March 28, 2024

Georgia State University To End Prison Education Program After Budget Cuts

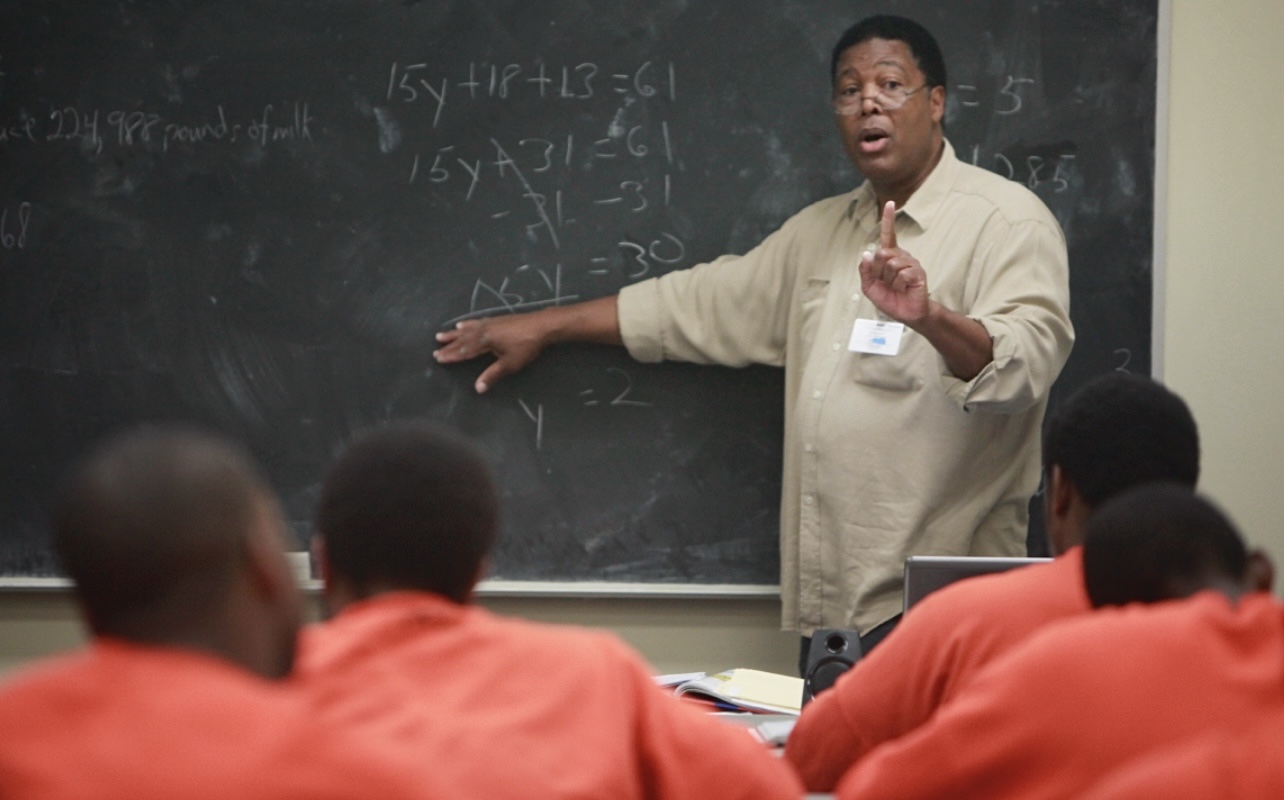

The university will shutter its prison education program this summer.

Georgia State University officials believe that a change in how Pell Grants are allocated plus a major budget decrease played a role in the university’s decision to shutter its prison education program this summer.

As Georgia State University Provost Nicolle Parsons-Pollard told WABE, “While the decision was not made lightly, it reflects the university’s commitment to responsible financial management and ensuring existing educational initiatives receive the necessary support and resources. These financial challenges make it difficult to allocate resources to new initiatives, including the PEP program.”

According to Parsons-Pollard, the university spends close to $200,000 a year to keep the program going.

As Georgia Recorder reported, difficulties in securing federal financial aid and a $24 million budget decrease by the Georgia General Assembly were cited as reasons the program is coming to an end. The university indicated that students currently enrolled in the program will be allowed to finish their courses.

Some faculty members are disappointed by the university’s decision. Katherine Perry, an English professor at Perimeter College, which is affiliated with GSU, told the outlet that the end of the program represented another disappointment for the incarcerated people it served.

“These students have been disappointed in their lives over and over and over again,” said Perry, one of three founders of the program since 2016.

Perry continued, “For me, it’s so important that they not put education in that bucket of things that let them down because that’s why most of them didn’t get their education before.”

Experts like Stacy Bell, an English professor at Emory University and a board member of the Georgia Coalition for Higher Education in Prison, are concerned about what this could mean for similar programs.

“We have the fourth largest prison system in the country and we have a really underserved population here,” Bell told the Recorder. “And without Georgia State, it raises really big questions about what’s happening to the higher education-in-prison movement here in Georgia.”

Pell Grants for the incarcerated had been banned since 1994, but that changed in 2020, when access to the federal financial aid program was restored. It kicked off a wave of new prison education programs at universities, like the one at Georgia State.

Kayla James, senior program associate with the Unlocking Potential initiative at the Vera Institute of Justice, a research and policy organization focused on matters relating to criminal justice, told Inside Higher Ed that these programs need greater racial equity. “We’re not going to see the true potential of what this really big opportunity is if we’re not thinking about everyone who’s interested in pursuing a degree having the opportunity to earn one,” James said. “We need to think about using a racial equity lens to improve the quality of these programs.”

Sultana Shabazz, dean of corrections education at Tacoma Community College’s Washington Corrections Center for Women campus, told the outlet that the Pell Grant for incarcerated students had to be used in a more judicious manner than their free-world counterparts.

“There’s only so much Pell. Once you use it, it’s gone,” said Shabazz, who also stressed the importance of talking to students about their career goals post-incarceration. “It’s imperative that we make strategic decisions based on what the population of a facility is looking for and [that] gives them the best set of options that doesn’t squander their Pell.”

Similar to James, Stanley Andrisse, a formerly incarcerated person who is now executive director of From Prison Cells to PhD, an organization that helps formerly incarcerated people start careers, believes that racial equity starts with who runs these incarcerated education programs.

“Formerly incarcerated and currently incarcerated people need to be part of the leadership of higher education institutions and community-based organizations moving Pell restoration forward,” Andrisse told Inside Higher Ed, noting that many prison education programs are often led by white women, despite many incarcerated people being Black and brown and also male. “If we don’t see that as a really integral part of this new era, we will not only be missing out on an opportunity but could be setting ourselves up for damaging situations.”

RELATED CONTENT: Mississippi Valley State University Becomes First HBCU To Offer Prison College Courses In Mississippi